By Shivangi Acharya and Alistair Smout

NEW DELHI/LONDON (Reuters) -Britain and India clinched a long-coveted free trade pact on Tuesday after tariff turmoil sparked by U.S. President Donald Trump forced the two sides to hasten efforts to increase their trade in whisky, cars and food.

The deal, between the world’s fifth and sixth largest economies, has been concluded after three years of stop-start negotiations and aims to increase bilateral trade by a further 25.5 billion pounds ($34 billion) by 2040.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi said the trade deal was “ambitious and mutually beneficial”. British Prime Minister Keir Starmer said the strengthened alliance would reduce trade barriers in a “new era for trade”.

Trump’s tariffs have prompted countries across the world to redouble efforts to seek new trade partners and people familiar with the UK-India talks said the turmoil had sharpened the focus to get a deal done.

The deal, which will lower tariffs on goods such as whisky, allow British firms to compete for Indian contracts and Indian workers to more easily work in Britain, is significant for both economies.

It marks India opening up its long-guarded markets, including automobiles, setting an early example for the South Asian nation’s likely approach to dealing with major Western powers such as the U.S. and the European Union.

It also represents Britain’s most significant trade deal since it left the EU in 2020, though the projected boost to British economic output from the deal, of 4.8 billion pounds a year by 2040, is small compared to the country’s gross domestic product of 2.6 trillion pounds in 2024.

India’s trade ministry said 99% of Indian exports would benefit from zero duty under the deal, including textiles, while Britain will see reductions on 90% of its tariff lines.

STOP-START

Talks over a free trade deal between India and Britain were initially launched in January 2022, and became a symbol of Britain’s hopes for its independent trade policy after Brexit.

But negotiations were stop-start, with Britain having four different prime ministers since that launch date and elections in both countries last year.

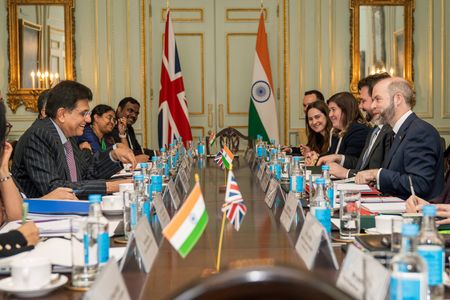

Britain’s Labour Party, elected last July, moved rapidly to conclude a deal after restarting negotiations in February, with last-minute talks between the countries’ trade ministers in London last week enough to get it over the line.

Britain’s Confederation of British Industry (CBI) said the deal was a “beacon of hope amidst the spectre of protectionism”.

Whisky tariffs will be halved from 150% to 75% before reducing to 40% by the deal’s 10th year, while auto tariffs will go from over 100% down to 10% under a quota system.

The Scotch Whisky Association said the deal would be “transformational” for the industry and the UK auto industry body SMMT said it appreciated the considerable effort of negotiators despite the apparent compromises made.

The governments did not publish the text of the deal, which is subject to legal checks, signing and ratification. Modi invited Starmer to India in a call welcoming the conclusion of the substantive talks.

The deal covers rules of origin regulations, giving access to manufacturers to lower tariffs even if they use inputs from other places and includes provisions on procurement allowing British firms to compete for more contracts in India.

BUSINESS MOBILITY

While Starmer is seeking to generate growth, political opponents criticised the deal for provisions it had on business mobility and social security amid public concern over immigration.

The free trade deal provides for easier mobility of certain professionals, while under a separate pact workers no longer have to make social security contributions in both India and Britain during temporary postings in the other country.

Kemi Badenoch, a former trade minister who now leads the opposition Conservative Party, said she had refused to sign a similar deal because of India’s demands on visa requests and social security.

Britain’s trade minister Jonathan Reynolds said the social security pact created a level playing field for India, and emphasised that Britain had rejected requests on more visas for students under the talks.

“There is no impact on the immigration system of the deal that we have agreed,” Reynolds told reporters, saying there were only “modest changes” on business mobility.

He said the deal involved gaining certainty for services over the regulations they faced, but efforts to include legal services in the deal came up short.

Meanwhile, financial services will be covered by talks over a bilateral investment treaty. While negotiations on that treaty were conducted in parallel with free trade talks, differences remain and so talks will continue.

Neither government mentioned Britain’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which could levy higher taxes on polluters from 2027 – a policy that India had sought exemption from as part of the talks.

($1 = 0.7472 pounds)

(Reporting by Shivangi Acharya in New Delhi and Alistair Smout in London; additional reporting by Sachin Ravikumar, Muvija M and Emma Rumney in London and Aftab Ahmed in New Delhi; Editing by YP Rajesh, Sharon Singleton, Gareth Jones and Emelia Sithole-Matarise)