By Alistair Smout, Andrew MacAskill and Andrew Gray

LONDON/BRUSSELS (Reuters) – Britain agreed the most significant reset of defence and trade ties with the European Union since Brexit on Monday after U.S. President Donald Trump’s upending of the global order pushed the two sides to move on from their acrimonious divorce.

Nearly nine years after it voted to leave the bloc, Britain, the second largest defence spender in Europe, will take part in joint procurement projects. The sides also agreed to make it easier for UK food and visitors to reach the EU, and signed a contentious new fishing deal.

Trump’s tariffs, alongside warnings that Europe should do more to protect itself, forced governments around the world to rethink trade, defence and security ties, bringing British Prime Minister Keir Starmer closer to France’s Emmanuel Macron and other European leaders.

Starmer, who backed remaining in the EU in the Brexit referendum, also bet that offering benefits to Britons such as the use of faster e-gates at EU airports will drown out the cries of “betrayal” from Brexit campaigner Nigel Farage.

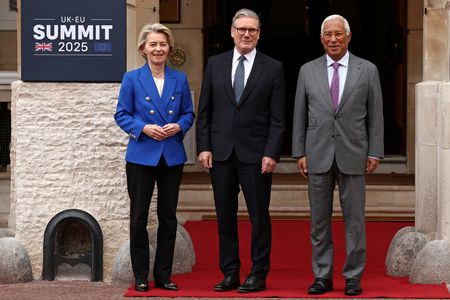

Flanked by EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and European Council President Antonio Costa, Starmer said the deal marked “a new era in our relationship”.

Von der Leyen said it sent a message to the world: “At a time of global instability, and when our continent faces the greatest threat it has for generations, we in Europe stick together.”

Britain said the reset with its biggest trading partner would reduce red tape for food and agricultural producers, making food cheaper, improve energy security and add nearly 9 billion pounds ($12.1 billion) to the economy by 2040.

It is the third deal Britain has struck this month, after agreements with India and the U.S., and while it is unlikely to lead to an immediate economic boost, it could lift business confidence, drawing much-needed investment.

At the heart of the reset is a defence and security pact that will let Britain be part of any joint procurement and pave the way for British companies including BAE, Rolls-Royce and Babcock to take part in a 150 billion euro ($167 billion) programme to rearm Europe.

On fishing, British and EU vessels will have access to each other’s waters for 12 years – removing one of the UK’s strongest hands in any future talks – in return for a permanent reduction in paperwork and border checks that had prevented small food producers from exporting to Europe.

In return, Britain has agreed to the outline of a limited youth mobility scheme, with the details to be hammered out in future, and it is discussing participation in the Erasmus+ student exchange programme.

The agreement was denounced by Farage and the opposition Conservative Party, which was in power when Britain left the bloc and spent years negotiating the original divorce deal.

HISTORIC REFERENDUM

Britain’s vote to leave the EU in a historic referendum in 2016 revealed a country that was badly divided over everything from migration and sovereignty of power to culture and trade.

It helped trigger one of the most tumultuous periods in British political history, with five prime ministers in office before Starmer arrived last July, and poisoned relations with Brussels.

Polls show a majority of Britons now regret the vote although they do not want to rejoin. Farage, who campaigned for Brexit for decades, leads opinion polls in Britain, giving Starmer limited room for manoeuvre.

But collaboration between Britain and European powers over Ukraine and Trump has rebuilt trust between the two sides after relations were badly damaged by years of arguments.

Rather than seek a full return to a pillar of the EU such as the single market, Starmer sought to negotiate better market access in some areas – a move that is often rejected by the EU as “cherry picking” of EU benefits without the obligations of membership.

Removing red tape on food trade required Britain to accept EU oversight on standards, but Starmer will argue that it is worth it to grow the economy and cut food prices. Trade experts said breaking the taboo of EU oversight for something that would benefit small companies and farmers was good politics.

Despite the agreement, Britain’s economy will remain significantly different from before it left the bloc. Brexit cost London’s financial centre thousands of jobs, has weighed on the sector’s output and reduced its tax contributions, studies show.

($1 = 0.8958 euros)

($1 = 0.7464 pounds)

(Writing by Kate Holton; additional reporting by Philip Blenkinsop in Brussels; Editing by Aidan Lewis, Ros Russell and Andrew Heavens)